Opinion of the Advocate-General

I - Introduction

1 By the questions it has referred to the Court for a preliminary ruling, the First Commercial Chamber of the Landgericht München I (Regional Court, Munich I) seeks guidance on the interpretation of Article 3(1)(c), the first sentence of Article 3(3) and Article 6(1)(b) of the First Council Directive of 21 December 1988 to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks (89/104/EEC) (1) (hereinafter `the Directive').

2 The questions have been raised in proceedings between Windsurfing Chiemsee Produktions- und Vertriebs GmbH (WSC), the plaintiff in the main proceedings (hereinafter `the plaintiff'), on the one hand and, in Case C-108/97, Boots- und Segelzubehör Walter Huber (hereinafter `the first defendant') and, in Case C-109/97, Franz Attenberger (hereinafter `the second defendant'), on the other. The proceedings have arisen as a result of the defendants' use of the mark `Chiemsee', which is registered in the name of the plaintiff, to distinguish their products.

II - Directive 89/104

3 Article 2 of the Directive states:

`A trade mark may consist of any sign capable of being represented graphically, particularly words, including personal names, designs, letters, numerals, the shape of goods or of their packaging, provided that such signs are capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings.'

4 Article 3, which sets out the grounds for refusal or invalidity of a mark, provides:

`1. The following shall not be registered or if registered shall be liable to be declared invalid:

...

(c) trade marks which consist exclusively of signs or indications which may serve, in trade, to designate the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, or the time of production of the goods or of rendering of the service, or other characteristics of the goods or service:

...

3. A trade mark shall not be refused registration or be declared invalid in accordance with paragraph 1(b), (c) or (d) if, before the date of application for registration and following the use which has been made of it, it has acquired a distinctive character. Any Member State may in addition provide that this provision shall also apply where the distinctive character was acquired after the date of application for registration or after the date of registration.

...'

5 Article 5, which relates to the rights conferred by a trade mark, provides:

`1. The registered trade mark shall confer on the proprietor exclusive rights therein. The proprietor shall be entitled to prevent all third parties not having his consent from using in the course of trade:

(a) any sign which is identical with the trade mark in relation to goods or services which are identical with those for which the trade mark is registered;

(b) any sign where, because of its identity with, or similarity to, the trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by the trade mark and the sign, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public, which includes the likelihood of association between the sign and the trade mark.

...'

6 Furthermore, Article 6, which relates to the limitation of the effects of the trade mark, provides:

`1. The trade mark shall not entitle the proprietor to prohibit a third party from using, in the course of trade,

...

(b) indications concerning the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, the time of production of goods or of rendering of the service, or other characteristics of goods or services;

...

provided he uses them in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters.'

III - Relevant national legislation

7 As is clear from the order for reference, the applicable law in Germany before transposition of the Directive and until 31 December 1994 was the Warenzeichengesetz (Trade Mark Law, hereinafter `the WZG'). Paragraph 4(2)(1) of the WZG specifically excluded from registration signs `which have no distinctive character or consist exclusively of ... words which contain indications of the kind, time and place of production, the quality or purpose ... of the goods'.

8 None the less, even signs which were devoid of distinctive character within the meaning of that provision were protected under Paragraph 4(3) of the WZG if they had gained `trade acceptance'.

9 Furthermore, the WZG recognised, in Paragraph 25 (`Ausstattungsschutz' - `protection of get-up'), the possibility of acquiring rights in a trade mark not by registration but by use of the mark and the effect of such use on the trade. According to the order for reference, Paragraph 25 uses the term `trade reputation' (`Verkehrsgeltung') to describe what is required.

10 The Directive was transposed into German law by the Markengesetz (Law on Trade Marks) which entered into force on 1 January 1995. (2)

11 Paragraph 8(2) of the Markengesetz, which corresponds to Article 3(1)(c) of the Directive, excludes from registration, inter alia, trade marks `which consist exclusively of ... indications which may serve in trade to designate the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin ... or other characteristics of the goods'.

12 Under Paragraph 8(3) of the Markengesetz, a trade mark which is precluded from being protected because it falls within Paragraph 8(2) (3) may still be registrable `if the mark, before the time of the decision on registration, as a result of its use for the goods ... in respect of which registration has been applied for, has gained acceptance in the trade circles concerned'.

13 Furthermore, under Paragraph 4(2) of the Markengesetz (which replaced Paragraph 25 of the previous law), it is possible to acquire rights in a mark by virtue of its use and the reputation it has acquired in the trade.

14 Under German case-law, the concept of `trade acceptance' (`Verkehrsdurchsetzung') is wider and more comprehensive than that of `trade reputation' (`Verkehrsgeltung'). Thus, the fact that a mark has been granted registration because it has gained trade acceptance necessarily means that it has acquired some kind of trade reputation - but the opposite is not necessarily true. In order to determine whether trade reputation or trade acceptance exists, a distinction must be drawn between those verbal and morphological aspects of a mark which are intrinsically distinctive and those which are not (such as descriptive names, particularly those designating geographical origin). The former in general justify the registration and protection of the mark whereas the latter must gain acceptance through use in the relevant trade circles. The level of trade acceptance or trade reputation varies from approximately 16% to 70%. The main method for establishing the level of acceptance or reputation is by survey. However, both German case-law and legal authors are reluctant to accept the recognition and protection of signs which need to be `left free', that is to say, if I have understood correctly, they resist the notion that one business should have a monopoly on signs which other businesses have an equal interest in using.

IV - Facts

15 The Chiemsee is the largest lake in Bavaria, with an area of 80 km2. It is a tourist attraction. Surfing is one of the activities carried on there. The surrounding area, called the Chiemgau, is primarily agricultural.

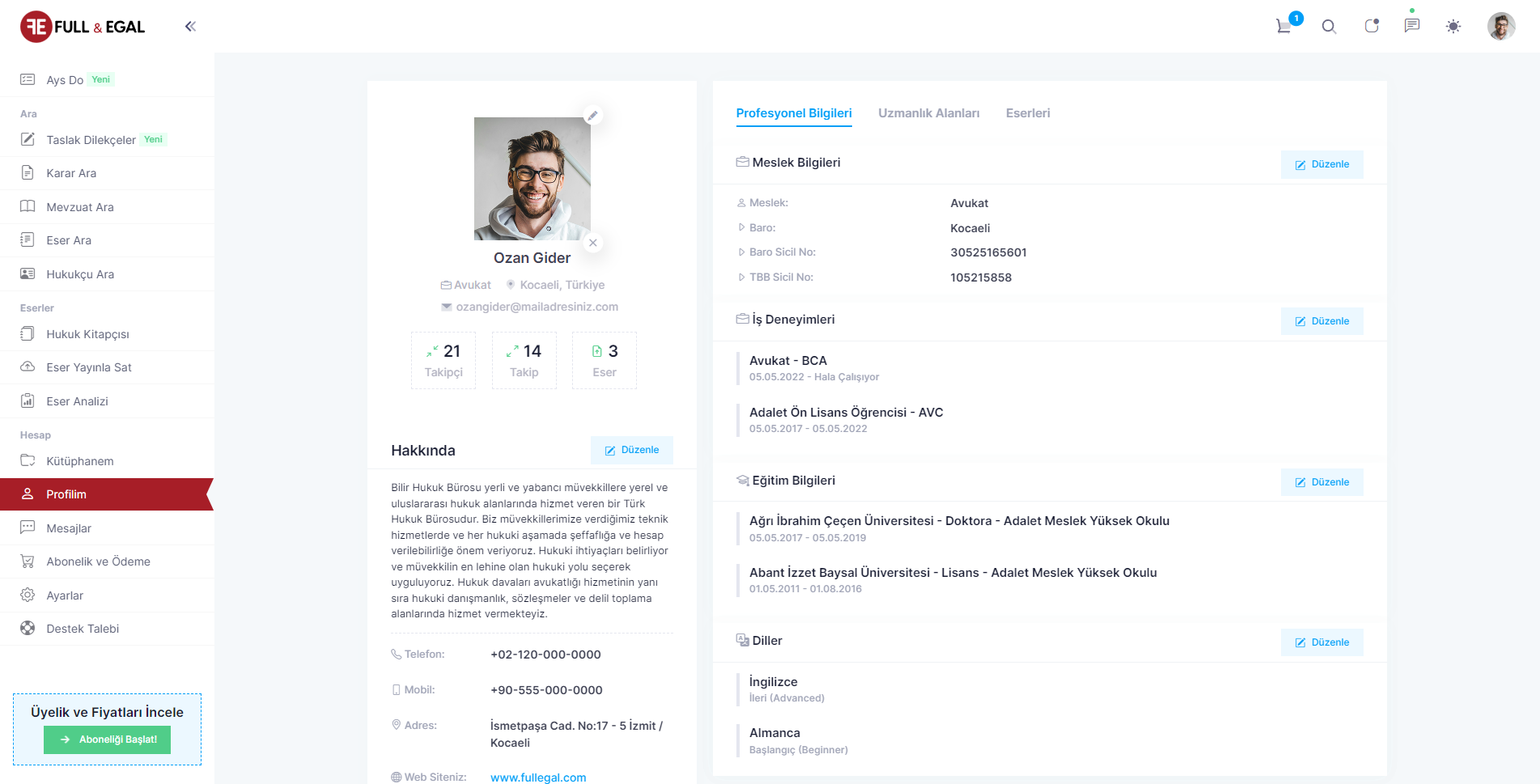

16 The plaintiff is based in Grabenstätt near the Chiemsee. It sells sports clothes and shoes as well as other sports fashion products, designed by a sister company which is also based near the Chiemsee, and manufactured in a different region. The plaintiff has been using the name of the lake to designate its products since 1990. Between 1992 and 1995, moreover, the plaintiff also registered the name as a trade mark in respect of its products as part of various graphic designs, in some cases with pictures (in particular a picture of a sportsperson diving, if I have interpreted it correctly) and additional wording such as `Chiemsee Jeans', `Windsurfing - Chiemsee - Active Wear', `By Windsurfing Chiemsee' and so forth. The marks are set out below in chronological order, as reproduced in the order for the reference:

A. Registration No/Mark Date of registration

2009617 17.2.1992

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

B.2009618 17.02.1992

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

C.2014831 01.06.1992

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

D.2043643 31.08.1993

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

E.2043644 31.08.1993

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

F.2086304 30.11.1994

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

G. 2901054 31.01.1995

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

17 As the national court observes, the competent German authorities both administrative and judicial have always considered that the term `Chiemsee' designates a geographical origin and that it is not therefore capable in itself of being registered as a trade mark. However, they allow it to be registered exclusively on the basis of the graphic representation of the mark, which differs in each case, and the additional features.

18 The first defendant is based in an area near the Chiemsee and sells, inter alia, sports clothes (such as tee shirts, sweat shirts and so on) albeit only since 1995. The products bear the distinctive sign `Chiemsee', which has not been registered as a trade mark and appears in the following graphic form:

(a)

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

19 The second defendant sells similar products to those sold by the first defendant on the outskirts of the Chiemsee. The products bear the distinctive sign reproduced at (a) above as well as the following signs, which are also not registered:

(b)

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

(c)

>REFERENCE TO A GRAPHIC>

20 In the main proceedings, the plaintiff challenged the use of the name `Chiemsee' by the defendants, claiming that, notwithstanding the differences in graphic representation, there was a risk of confusion with the name used by it since 1990 which it has registered as a trade mark and which is known in the trade.

21 The defendants, on the other hand, contend that the term `Chiemsee' is not capable of protection because it is an indication of geographical origin which must remain available to everybody, and that accordingly its use in a different graphic form cannot create any risk of confusion.

22 That being so, the national court considers it necessary to refer the following questions to the Court:

`1. Questions relating to Article 3(1)(c)

Is Article 3(1)(c) to be understood as meaning that it suffices if there is a possibility of the designation being used to indicate the geographical origin, or must that possibility be likely in a particular case (in the sense that other such undertakings already use that word to designate the geographical origin of their goods of similar type, or at least that there are specific reasons to believe that that may be expected in the foreseeable future), or must there even be a need to use that designation to indicate the geographical origin of the goods in question, or must there in addition also be a qualified need for the use of that indication of origin, for instance because goods of that kind, produced in that region, enjoy a special reputation?

Is it of significance for a broader or narrower interpretation of Article 3(1)(c) with respect to geographical indications of origin that the effects of the mark are restricted under Article 6(1)(b)?

Do geographical indications of origin under Article 3(1)(c) cover only those which relate to the manufacture of the goods at that place, or does trade in those goods at that place or from that place suffice, or in the case of the production of textiles does it suffice if they are designed in the region designated but then manufactured under contract elsewhere?

2. Questions on the first sentence of Article 3(3):

What requirements follow from this provision for the registrability of a descriptive designation under Article 3(1)(c)?

In particular are the requirements the same in all cases, or are the requirements different according to the degree of the need to leave free?

Is in particular the view hitherto taken in the German case-law, namely that in the case of descriptive designations which need to be left free, trade acceptance in more than 50% of the trade circles concerned is required and is to be demonstrated, compatible with that provision?

Do requirements follow from this provision as to the manner in which descriptive character acquired by use is to be ascertained?'

V - Substance

A - The first question

23 By the first and third limbs of the first question referred, which must be considered together, the national court is essentially asking whether, and in what circumstances, a geographical name can constitute a trade mark and, if it can, the extent to which such a trade mark is protected vis-à-vis third parties.

24 In order to answer that question, it is first of all necessary to recall the objective of the Directive and the rationale for according a trade mark protection.

25 As the first and third recitals make clear, the Directive is intended to achieve an initial level of harmonisation of the differing trade mark laws of the Member States, as the disparities which exist may impede the free movement of goods and the freedom to provide services and may distort competition within the common market.

26 To that end, the Directive, most importantly, lays down common rules for the registration of trade marks and, where appropriate, for establishing their invalidity a posteriori and sets out the scope and limitations of the protection conferred by a trade mark, leaving it to Member States to determine the details, particularly those relating to procedure.

27 The main purpose of the system adopted by the Community legislature is to safeguard and protect the essential function of the trade mark. That function, as set out particularly in the seventh recital in the preamble and in Articles 2, 3(1)(b) and 3(3), 5(5) and 10(2)(a) of the Directive is, first, to identify an undertaking's goods and to distinguish them from other similar products (distinguishing function of the trade mark) and, secondly, to establish a link between them and a particular undertaking (guarantee of origin).

As the Court has pointed out on more than one occasion, `the essential function of the trade mark ... is to guarantee to the consumer or end user the identity of the trade-marked product's origin by enabling him to distinguish it without any risk of confusion from products of different origin'. (4)

28 In my view, it is in the light of precisely that function of trade marks that Article 3(1) of the Directive makes lack of distinctive character an independent ground for refusal or invalidity of a mark (paragraph (b)) but also provides for a more specific ground for invalidity or refusal in respect of marks which consist exclusively of descriptive indications (paragraph (c)) or which have become customary in the current language or in the trade (paragraph (d)).

29 Although in the text of the Directive, paragraphs (c) and (d) are, strictly speaking, distinct from paragraph (b), in essence they describe more particular or more specific or simply more typical instances of lack of distinctive character in a mark which explain and clarify the general concept of lack of distinctive character but do not introduce new or fundamentally different ideas. (5) The same conclusion follows if Article 3(1) is interpreted alongside Article 3(3), under which a trade mark is not to be refused registration or declared invalid under paragraphs (b), (c) or (d) of Article 3(1) if it has subsequently acquired a distinctive character by reason of the use which has been made of it. In other words, in the circumstances set out in those paragraphs, which are dealt with together in Article 3(3), the trade mark subsequently acquires the quality which it initially lacked and the absence of which prevented it from being registered or enabled it to be struck off the register - namely distinctive character. Accordingly, it may be assumed that those cases which are not specifically mentioned in paragraphs (c) or (d) of Article 3(1) fall within paragraph (b). (6)

30 I now turn to Article 3(1)(c). It is clear from the wording itself of this provision that three conditions must be fulfilled for a trade mark comprising a geographical indication to fall within its scope. First, the trade mark must consist exclusively of a geographical indication; secondly, the indication must serve in trade to designate geographical origin; and thirdly, the geographical origin must constitute a characteristic of the goods. More specifically:

(a) Exclusivity

31 First of all, it should be noted that only trade marks which consist `exclusively' of purely descriptive signs or indications fall within the provision. Accordingly, compound trade marks which are composed of one or more words, images or representations in addition to the descriptive indications which, whether separately or in combination with the descriptive indication, give the mark a distinctive character, do not. On that basis, trade marks such as those belonging to the plaintiff which appear at A, B, C, D and E above and those belonging to the second defendant which appear at (c) above do not to my mind fall within the contested provision. (7)

32 Therefore, the problem arises in cases such as those in the main proceedings where marks consist exclusively of a geographical indication such as the plaintiff's marks which appear at F and G above and the defendant's marks which appear at (a) and (b) above.

(b) Geographical origin

33 As stated earlier, it is clear from the order for reference that the German authorities regard a geographical indication such as the name `Chiemsee' as descriptive and therefore not in itself capable of registration. However, they still allow it only because its graphic representation differs in each case. On that point, the national court refers to the plaintiff's marks appearing at F and G above which differ from one another only in their particular graphic representation of the word `Chiemsee', the word of which they consist.

34 I believe that approach to be misconceived. If the only or principal constituent element of a mark is a geographical term, the question whether it may serve to designate geographical origin within the meaning of Article 3(1)(c) must be assessed according to objective criteria, taking into account the meaning conveyed by the actual term itself. The main or only constituent element of marks such as those appearing at F and G and (a) and (b) above is the verbal element, that is, the acoustic impression made by the term `Chiemsee' upon the ear of the listener or the imagination of the viewer. The visual impression made by each of those marks is of limited scope and plays what is very much a secondary role in the perception of the mark because it is limited to differing graphical representations of the same word (in the mark appearing at (b) above, the word `Chiemsee' simply appears inside an ellipse which is darker in colour), without other words or pictures reinforcing or highlighting the mark. The result of this is to cause confusion as to the relationship between the marks, because the impression is given that they are simply variants of the same mark and, by extension, that the goods originate from the same commercial undertaking which owns the mark. In conclusion, a different graphic representation of the same word does not constitute a distinctive or additional element tacked on to the geographical term so as to create a new `compound' mark, as the national court mistakenly supposes. Such representations are simple marks which are either identical or similar to one another (such as the marks appearing at F and (a) above), with the result that they give the impression of being variants of the same mark.

If the opposite view were taken, the result would be a limitless proliferation of trade marks consisting of the same word, since the number of ways in which a word can be graphically represented is infinite. However, that would create utter confusion in the market and lead to an increase in conflicts between marks, which cannot have been the intention of the Community legislature. (8)

35 Next, it should be noted that Article 3(1)(c) does not exclude all geographical terms without exception.

Clearly, therefore, imaginary, mythical or figurative geographical names (such as `Thule', `Utopia', `No Man's Land', `Atlantis', and so on) do not fall within Article 3(1)(c) since they cannot designate any geographical origin.

The same holds true for the names of towns, places or areas which have become obsolete or have changed over the centuries (such as `Byzantium', `Dacia', `Lutetia', `Babylon' and so on).

Furthermore, where it is illogical or improbable that a geographical name indicates the geographical origin of the goods in question, it cannot fall within Article 3(1)(c). The example usually given here is that of the `Mont Blanc' trade mark for pens (because nobody could logically suppose a pen to originate from the mountain in question), `Pôle Nord' (`North Pole') for bananas (because bananas cannot be grown in the prevailing climate at that latitude) and so on.

Similarly, geographical terms which are completely unknown cannot fall within the provision, that is, terms referring to places unknown to the general public whether within or outside the Member State in which the question of protection of the trade mark arises, because the public is in any event not in a position to connect the goods in question with the places designated by the geographical indications concerned.

36 In all the above cases, the geographical term does not designate the geographical origin of the goods, either because of its nature or because of the circumstances, and can therefore legitimately be used as a trade mark. That is so because the connection between the `designator' (the name itself) and the `designee' (the thing to which the name refers) is arbitrary, (9) that is to say, so original and unexpected that it does identify the goods and distinguish them from equivalent goods made by other undertakings. In such cases, therefore, the trade mark does in principle perform its distinguishing function.

37 It follows from the foregoing that Article 3(1)(c) does not prevent the use of all geographical terms in general, but only of some of them. In my view, it prevents the use of those geographical terms which, at the time when the mark was applied for, were not yet consolidated and could constitute `indications of origin' or `designations of origin' within the specific meaning of those legal terms under Community law at the time when the Directive was adopted.

Indeed, if the Community legislature had intended to exclude indications which simply designate geographical origin, it would have referred to signs which designate such origin, because that is the primary function of geographical indications both in the current language and in trade. The fact that the Directive uses the circumlocution `which may serve, in trade, to designate ...' in my view denotes that such indications have the specific meaning set out above.

38 The terms `indications of origin' and `designations of origin' had a precise meaning in Community law well before they were defined by the Community legislature in Council Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92 (10) at least in the sector of agricultural products and foodstuffs.

39 The Court has, in its case-law, stated what is meant by these terms, particularly when interpreting Article 36 of the EC Treaty. In the cases concerned, the question which arose was whether restrictions on the free movement of goods imposed by national law could be justified on grounds of the protection of rights which constitute the specific subject-matter of industrial and commercial property, and in particular `indications of origin' and `designations of origin'.

40 Thus, in its judgment in Commission v Germany, (11) the Court held that: `Whatever the factors which may distinguish them, the registered designations of origin and indirect indications of origin referred to in that directive always describe at the least a product coming from a specific geographical area.

To the extent to which these appellations are protected by law they must satisfy the objectives of such protection, in particular the need to ensure not only that the interests of the producers concerned are safeguarded against unfair competition, but also that consumers are protected against information which may mislead them.

These appellations only fulfil their specific purpose if the product which they describe does in fact possess qualities and characteristics which are due to the fact that it originated in a specific geographical area.

As regards indications of origin in particular, the geographical area of origin of a product must confer on it a specific quality and specific characteristics of such a nature as to distinguish it from all other products' (point 7).

41 Furthermore, in its judgment in Prantl, (12) which was clarified by its judgment in Exportur, (13) the Court acknowledged that a bottle containing a product could constitute an `indirect designation of geographical origin' (the case related to the `Bocksbeutel' used by wine growers in Franconia and Baden for the presentation of their wines). It is clear from that judgment that such an indication may be protected if it has been used for a long period of time by producers from a specific region in order to distinguish their products, but that Articles 30 and 36 of the EC Treaty prohibit national legislation allowing only certain domestic producers to use such bottles if similar bottles are also traditionally used by producers in other Member States, and have been for a long period of time, to market their wines.

42 In Exportur, to which I have just referred, the question arose whether French companies had the right to produce and sell in France confectionery for which they were using the names `Alicante' and `Jijona' (names of Spanish towns), which a Spanish company had been using for a long period of time to describe similar products manufactured by it. (14) In the judgment given in that case, the Court drew the following distinction between the concept of `indications of provenance' and `designations of origin': <